This is, at its root, the story of two cantankerous men getting in each other’s way. P.J. Carlesimo annoyed and eventually lost every locker room he was tasked with galvanizing, and Latrell Sprewell alienated enough teammates to fill the rosters of several expansion teams.

In 1994, when Carlesimo left Seton Hall to coach in the professional ranks, he was immediately in over his head, foundering without the benefit of the gross power imbalance between coach and player that college ball provides. The Blazers had moved on from Rick Adelman for going 47-and-35 with a talented squad the previous season. Carlesimo went 44-and-38, and the atmosphere around the team went rotten the following year. Cliff Robinson and James Robinson got in an Eastern Promises-style brawl as they were headed to the showers after practice. Gary Trent and Dontonio Wingfield were involved a less spectacular scuffle. The team nosedived after the all-star break, losing seven of nine and dropping to 26-and-33.

Rod Strickland, the team’s second-best player behind Uncle Cliffy, loathed Carlesimo and had run completely out of patience, ignoring the coach’s instructions and cussing him out with regularity. He demanded a trade in February of 1996, and when the Blazers didn’t deal him away, he simply stopped showing up for work, missing over two weeks’ worth of practices and games before returning to the fold in mid-March.

The portrait of Carlesimo that emerges, if you examine comments from his players, is of a guy who couldn’t read the room. He believed good coaching involved relentless critique and failed to understand that sometimes you don’t want to hear it from your boss.

It’s no surprise that Strickland explains this most directly: “he’s not really a yeller or a screamer; he’s just annoying. He doesn’t know how to deal with men. He’s used to dealing with college kids.” But even P.J.’s supporters seem lukewarm on him. When Buck Williams was asked if the entire Portland team was behind Carlesimo: “well, quite obviously not. But players don’t have to love a coach in order to play hard and win.” Cliff Robinson: “I don’t want to judge [P.J.] too much. Does every guy in this locker room love him? Doesn’t really matter. This isn’t really a happy team right now, but it’s mostly because we’re losing, not because of who the coach is.” There are, pointedly, not many comments from Carlesimo’s charges that express love or admiration for him. Other coaches like him—Gregg Popovich is a longtime friend and supporter—but on the whole, players never have.

When Latrell Sprewell choked Carlesimo in December of 1997, it wasn’t like the entire team rushed to stop him. There was a moment when some of them were caught marveling at the scene, as if one of their daydreams was suddenly manifesting itself. Huh, I was just thinking about this the other day.

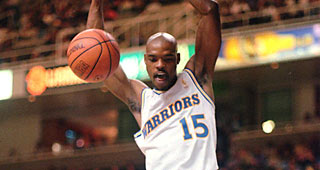

Spree attacked P.J. because the coach implored him to “put a little mustard on [the] passes” he was tossing too lazily in a mid-practice drill. Spree told P..J to leave him alone, P.J. got in his face about it, and the six-foot-five guard tackled Carlesimo, pinning him to the floor and choking him for 10 to 15 seconds before his colleagues intervened. Spree was ejected from practice but came back 20 minutes later to scream some more at Carlesimo, and throw a few punches.

This was the culmination of Sprewell’s productive but prismatically unhappy tenure in Oakland. He had been a dark presence for a while, an intensely inward and moody person who didn’t easily connect with others. He was, even in 1997, still stewing over the fact that the Warriors had traded away his friends Billy Owens and Chris Webber in the summer of 1994. He got in a practice fight with Jerome Kersey in 1995 that ostensibly ended with Spree storming off the court and threatening to retrieve a gun from his car. He then returned to the facility angrily wielding a two-by-four.

“He always seemed to have this hatred inside him,” Rony Seikaly told the press after the Carlesimo incident.

He hated sharing a backcourt with Tim Hardaway. The two weren’t on speaking terms by the time Hardaway was traded to Miami in 1996. He hated playing for Don Nelson, which is genuinely anomalous. Spree was the head of a revolt that forced Nellie to resign partway through the 1995-96 season.

It was no surprise the Spree didn’t take to Carlesimo’s inexhaustibly negative coaching style, but he was also thoroughly unprofessional leading up to the attack. He loafed through practices and even certain games. He missed a team flight from Oakland to Salt Lake City and didn’t show up in Utah until the next day. He called Carlesimo “a [bleeping] joke” after P.J. told him he would be coming off the bench against the Detroit Pistons. There is being yourself, and there is being a disruptive jerk. Spree was always the first thing and often the second.

The Warriors tried to void his contract. David Stern tried to kick him out of the league for a year. An arbitrator stepped in and reduced the punishment: a five-month suspension, and Spree got to keep his deal. Of course he was done in Golden State. They sent him to the Knicks for John Starks, Chris Mils, and Terry Cummings. Chastened slightly by the immense criticism he had suffered, Spree fit in fine on Jeff Van Gundy’s Knicks, though it took him some time to get acclimated: his suspension expired shortly before the league’s collective bargaining agreement did the same. Just as Spree was settling into a groove in New York, Carlesimo was fired by the Warriors after starting the 1999-00 season 6-and-21. He was the wronged party in their violent spat, but that didn’t make him a good coach.

There is maybe nothing profound to say about Sprewell and Carlesimo. A big contemporary cover story in Sports Illustrated—which was highly useful for the purposes of this piece—feints at racial commentary, but doesn’t really endeavor to make any. There’s a labor vs. management angle, but it’s not like Spree was being grossly mistreated. His actions were hardly justified, and the punishment eventually settled on by a third party was fair. Two exceptionally ornery guys got in an argument and one took it way too far. That wasn’t the end of it, but that might be where the meaning stops.

On December 25th, 2001, Carlesimo was calling a game at the Garden and Sprewell was starting for the Knicks. He went over, shook P.J.’s hand, and wished him a Merry Christmas. The two did not then make post-game dinner plans, but Spree told reporters he was willing to “let bygones be bygones.” Carlesimo, however he felt privately about Sprewell, never went out of his way to bash the player who attacked him. In short, they got over it and proceeded with their respective careers.

Sometimes cataclysms are just cataclysmic—not instructive or even all that significant. The effects over time are less permanent than they seemed like they would be in the moment. Latrell Sprewell is one thing—the coach-choker—and many others, and P.J. Carlesimo is similar. Violence generally occurs when people run out of things to say, and then afterwards, people say a lot of stuff trying to explain the violence itself. It’s typically just stupid and ugly and embarassing. The principals understandably want to move on. That’s what Spree and Carlesimo did, to the extent that they were allowed to. Nothing was overcome, nothing truly resolved. But they got through it.

More Histories: Atlanta Hawks | Boston Celtics | Brooklyn Nets | Charlotte Hornets | Chicago Bulls | Cleveland Cavaliers | Dallas Mavericks | Denver Nuggets | Detroit Pistons | Houston Rockets | Golden State Warriors | Indiana Pacers | Los Angeles Clippers | Los Angeles Lakers | Memphis Grizzlies | Miami Heat | Milwaukee Bucks | New Orleans Pelicans | New York Knicks | Oklahoma City Thunder | Orlando Magic | Philadelphia 76ers | Phoenix Suns | Portland Trail Blazers | Sacramento Kings | San Antonio Spurs | Toronto Raptors | Utah Jazz | Washington Wizards