While young players often make their NBA reputations in the Rookie of the Year race, it’s impossible to fairly evaluate them until their sophomore campaigns.

The transition between college and the pros is the biggest jump players make in their careers. NCAA teams play 30 to 40-game seasons spread over six months; NBA teams (normally) cram 82 games into the same period of time.

Even players in powerhouse conferences like the Big East only face NBA-caliber competition once or twice per week, while they might face NBA players at their position a handful of times all season. At the next level, they’re facing NBA players every single night.

Against amateur competition, they can coast defensively because they are such superior athletes. There aren’t any 6’9, 275 small forwards with 40 inch verticals barreling down the lane in college, and there certainly aren’t any 6’11, 265 centers with 40 inch verticals annihilating weak shots at the rim.

And while most dominated the ball their whole lives, unless they were drafted at the top of the lottery, NBA rookies have to learn how to be efficient off-ball role players.

The off-court transition is just as huge: in college, players are coddled by coaches whose job status depends on keeping them on campus by developing a “family atmosphere” around their program. In the NBA, they are living on their own for the first time, thrust in an unfamiliar city half-way across the country, with highly-publicized seven-figure incomes that make them a target for con men and gold-diggers looking to make a quick buck.

By the time they hit the dreaded “rookie wall”, often for a team going nowhere full of veterans trying to pad their statistics in order to get one more contract, their first year has become mostly about survival.

Last season, my list of second-year breakout players (guys who did not play in the Rookie Game on All-Star Weekend) was Serge Ibaka, Jrue Holiday, DeMar DeRozan, Jeff Teague, Rodrigue Beaubois and Earl Clark. Here are five guys that could have similar types of breakout years in 2011-2012:

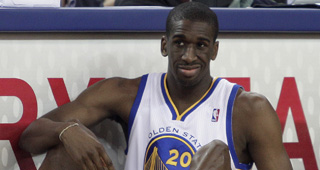

• Ekpe Udoh, 6’10 245 PF/C, Golden State Warriors:

Udoh missed the first half of his rookie season with a broken wrist, and he was barely featured in the Warriors’ offense, with a miniscule usage rating of 12.5, when he came back. But his per-36 minute average of 3.0 blocks was very interesting.

An athletic big man with a 7’5 wingspan and a max vertical of 33 inches, Udoh displayed a considerable amount of skill for a player his size in leading Baylor to the school’s first Elite Eight in 2010, averaging 2.7 assists a game while shooting 69% from the free-throw line.

On a Golden State team desperately in need of frontcourt defense, Udoh’s shot-blocking and rebounding will get him on the floor. Offensively, his athleticism at the rim, as well as a developing mid-range jumper, should make him a good pick-and-roll partner with the Warriors’ bevy of guards.

• Gordon Hayward, 6’8 210 SF, Utah Jazz

After struggling to get consistent minutes as a 20-year-old on a Utah Jazz team that ended up losing its coach and its franchise player halfway through the season, Hayward came on strong toward the end of the season.

A pure shooter with great ball-handling skills at 6’8, he displayed uncommon offensive efficiency for a young player -- shooting 48.5% from the field and 47.3% from the three-point line.

He doesn’t have the athleticism to be a great defender or a primary shot-creator, but he’s a smart player who should benefit from playing off a deep group of Utah big men -- Al Jefferson, Paul Millsapp, Mehmet Okur, Enes Kanter and Derrick Favors -- while relying on Josh Howard and Raja Bell to take the more difficult defensive assignments on the perimeter.

• Avery Bradley, 6’3 180 G, Boston Celtics

After playing as a freshman for a talented Texas team that imploded through no fault of his own and then undergoing ankle surgery before the start of his rookie year, the 21-year-old Bradley has mostly been forgotten nationally.

But there’s a reason that ESPN rated him higher than John Wall while both were in high school, and guys with great recruiting pedigrees often over-perform their draft status. He’s an elite athlete with a 6’7 wingspan and the product of a Longhorn system that emphasizes hard-nosed individual defense.

He’s not a true point guard, but he displayed a consistent three-point shot in Austin (shooting 37.5% on 112 attempts) while also possessing the ball-handling ability to get to the rim and do things like this.

Bradley should be able to provide perimeter athleticism for an aging Boston roster, and Celtics GM Danny Ainge has shown a good eye for talent in the draft: taking Al Jefferson at 15, Rajon Rondo at 21, Delonte West at 24, Tony Allen at 25, Kendrick Perkins at 27, Glen Davis at 35 and Ryan Gomes at 50.

• Kevin Seraphin, 6’9 260, PF/C, Washington Wizards

A wide-bodied big man with a 7’3 wingspan, Seraphin can provide bulk for a Washington frontcourt made up primarily of long, lean athletes (Javale McGee, Andray Blatche and rookies Chris Singleton and Jan Vesely).

At 21-years-old, he averaged 8.7 points and 8.6 rebounds per-36 minutes while displaying flashes of a low-post game and a perimeter stroke, as he shot 71.0% from the free-throw line. And in a match-up with a great Spanish front-line featuring the Gasol brothers and Ibaka in Eurobasket 2011, Seraphin scored 18 points on 8-for-11 shooting.

• Devin Ebanks, 6’9 215, F, LA Lakers

Lost amid the Lakers involvement in the Chris Paul and Dwight Howard sweepstakes is the fact that the team has still not addressed the poor perimeter defense that sunk their hopes in the 2011 NBA Playoffs. Ebanks, an athletic 6’9, 210 forward with a 7’0 wingspan who often defended college point guards, slipped in the draft because he can’t shoot from the perimeter.

But, with the Lakers adding two big men who can stretch the floor (Josh McRoberts and Troy Murphy) to their second unit, they can live with Ebanks’ poor shooting ability. Right now, their only other perimeter player with any athleticism is Matt Barnes.